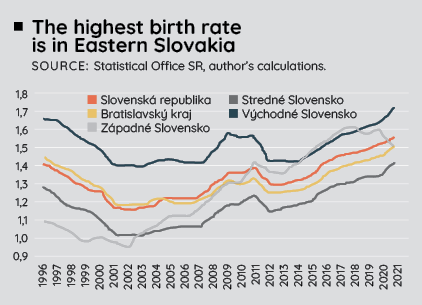

For the time being, companies in Slovakia are only facing a shortage of labor with a specific (high-quality) education, but figures on the overall fertility rate indicate that there will be fewer people on the labor market overall in the foreseeable future. Namely, not enough children have been born for a long time to stabilize the size of the population - the number of children per female has only recently risen above 1.6, but we would need to get to 2.1 to maintain the status quo. At the same time, Eastern Slovakia has the best trend in this regard, spearheaded by the Kežmarok and Sabinov districts, even though Bratislava was equal to it for a few years. Central and especially Western Slovakia are dying out. Due to the low birth rate, the size of the working age population in Slovakia has been declining since 2010. After the advent of strong years, the size of this population first increased from 3,601 thousand in 1996 to 3,929 thousand in 2010, but then returned to 3,635 thousand in 2021, almost to the level of 1996. In Eastern Slovakia, compared to 1996, the size of the working age population increased by 5 percent in 2021, reaching 1,058 thousand people. In Western Slovakia, on the other hand, it fell by 4 percent to 1,221 thousand people. The fastest growing districts were Senec with an increase of 87 percent, Námestovo with 30 percent and Košice-okolie and Kežmarok with 29 percent.

Due to the low birth rate, the size of the working age population in Slovakia has been declining since 2010. After the advent of strong years, the size of this population first increased from 3,601 thousand in 1996 to 3,929 thousand in 2010, but then returned to 3,635 thousand in 2021, almost to the level of 1996. In Eastern Slovakia, compared to 1996, the size of the working age population increased by 5 percent in 2021, reaching 1,058 thousand people. In Western Slovakia, on the other hand, it fell by 4 percent to 1,221 thousand people. The fastest growing districts were Senec with an increase of 87 percent, Námestovo with 30 percent and Košice-okolie and Kežmarok with 29 percent.

And it will get worse. In 2040, the size of the working age population in Slovakia will decrease by 9 percent compared to 2021. In Western Slovakia by 16 percent, in Central Slovakia by 13 percent and in Eastern Slovakia by 4 percent. In the smallest Bratislava region, it will be 0.7 percent higher, but only at the level of 475 thousand people. (Šprocha at al., 2019)

The situation will be saved by the Roma population, which according to available data has a much more favorable population curve than the rest of the country. According to demographic estimates, the share of children younger than 15 within the majority is 17 percent, but within the Roma population it reaches 37 percent (Vaňo, 2002). This is also confirmed by the latest sample findings, which state that while 62 percent of the majority households in Slovakia are childless, up to 74 percent of Roma households live with children (Grauzelová and Markovič, 2020). Due to these trends, we can estimate that the Roma population will increase its share of the working-age population from 7.6 percent in 2019 to 11 percent in 2030 (Šprocha, 2014). The demographic structure of the Roma and the majority population is expected to gradually level off in the coming decades. However, for now there is peace on the labor market. Compared to 1998, the size of the labor force (i.e., the number of employed together with unemployed job seekers) increased by 8 percent, to 2,709 thousand people. The highest increase by 10 percent to 766 thousand people was recorded in Eastern Slovakia. In Western Slovakia, there was an increase of 7 percent to 927 thousand people. So there are plenty of workers and job seekers - and there could be more, especially in the East.

However, for now there is peace on the labor market. Compared to 1998, the size of the labor force (i.e., the number of employed together with unemployed job seekers) increased by 8 percent, to 2,709 thousand people. The highest increase by 10 percent to 766 thousand people was recorded in Eastern Slovakia. In Western Slovakia, there was an increase of 7 percent to 927 thousand people. So there are plenty of workers and job seekers - and there could be more, especially in the East.

But here’s the first twist. While the activity rate, i.e., the share of the labor force in the total working-age population, has increased from 69 percent to 75 percent over the last 22 years in Slovakia overall, and has reached 81 percent in the Bratislava region, it has only reached 71 percent in Eastern Slovakia. In fact, in the East, the participation of the working-age population in the labor market has not changed much in 22 years, with an increase of only 3 percentage points. Our available workforce is growing, but ultimately remains passive.

A more enthusiastic picture can be drawn when talking about the number of workers in Slovakia, which has increased by 19 percent since 1999 to 2,522 thousand people, while the highest increase was in Eastern Slovakia, by 24 percent to 682 thousand people. At the same time, the number of unemployed fell sharply by 53 percent to 187 thousand in Slovakia overall and by 41 percent to 84 thousand in Eastern Slovakia.

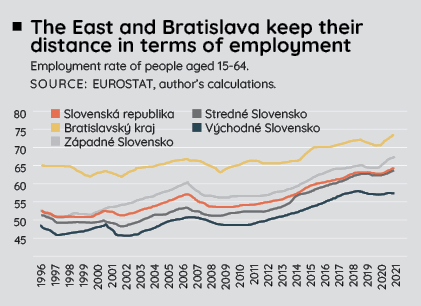

But here’s the second twist. The employment rate, which is the working part of the working age population, remains low compared to successful new EU Member States, despite rising by 8 percentage points to 69 percent since 1998. Romania, Croatia and Bulgaria recorded lower employment rates, while Estonia and the Czech Republic reached 75 percent. The Bratislava region, with an employment rate of 79 percent, together with the adjacent Western Slovakia with 73 percent, do not balance out the Center with 69 percent and especially the East with 63 percent. Despite significant improvements in Eastern Slovakia, only a relatively small proportion of people work there. This is confirmed by the list of districts with the estimated lowest employment rate in Slovakia, where ten of the top twelve are in the East: Kežmarok, Sabinov, Sobrance, Košice-okolie, Gelnica, Vranov nad Topľou, Michalovce, Levoča, Trebišov and Spišská Nová Ves. In the end, most of these districts also entered the state support scheme, the so-called “the least developed districts” scheme, because of their high unemployment rate. The East and Bratislava keep their distance in terms of employment

The East and Bratislava keep their distance in terms of employment

So what awaits Eastern Slovakia in 2030 and 2040? In other words, how high should its employment rate be in order to secure the same number of workers from “domestic sources” in the face of declining population? We estimate that in 2030, the Bratislava region would suffice with an employment rate of 77 percent, because its population is growing. Eastern Slovakia would need 70 percent. In 2040, Bratislava would need an employment rate of 81 percent and the East 74 percent, which doesn’t seem like much. But there’s another, the third twist.

Eastern Slovakia would need to significantly increase its activity rate from the current 71 percent to reach an employment rate of 70 percent in 2030 and 74 percent in 2040. If we want to increase employment in the East, we must first bring discouraged people who are no longer looking for work to the labor market. And we also need to consider the effects of skills and migration.

Bratislava, but also Western and Central Slovakia will attract more workforce from the East. Namely, in order to maintain the number of employees from 2019 in 2030, Western Slovakia would have to increase its employment rate to 78 percent and the Center to 75 percent. In 2040, the requested increase would need to move up to 86 percent and 81 percent, respectively. And this does not seem realistic from domestic sources, at least not without fundamental changes in labor and education market policies.

The second factor is the increasing risk for Eastern Slovakia in connection with the Russian aggression, which may increase the outflow of the working-age population abroad. The influx of Ukrainian labor in the form of refugees seems to be a temporary phenomenon – it cannot be expected that a considerable number of Ukrainian citizens would remain in Slovakia after the end of the conflict. The solution for Eastern Slovakia should be the integration of its large Roma population. At the same time, the demands on the qualifications of employees are rising faster and faster, so it will become more and more difficult if the integration does not start immediately. Problems already arise at the level of early childhood education. Children from marginalized Roma communities would need support in the early age, but paradoxically, they are the least likely to partake in early childhood programs or enroll in kindergartens. A huge proportion of these children are then transferred to special education, from where at the end of the day there is no way back to the open labor market. As many as 19 percent of the Roma population have only completed a special primary school, and another 60 percent have only a primary education. Our school system is one that does not reduce, but on the contrary, increases inequalities among children. It can be said that children from marginalized communities come out of schools even more excluded from the mainstream than when they entered them. (Ministry of Finance, 2020)

The solution for Eastern Slovakia should be the integration of its large Roma population. At the same time, the demands on the qualifications of employees are rising faster and faster, so it will become more and more difficult if the integration does not start immediately. Problems already arise at the level of early childhood education. Children from marginalized Roma communities would need support in the early age, but paradoxically, they are the least likely to partake in early childhood programs or enroll in kindergartens. A huge proportion of these children are then transferred to special education, from where at the end of the day there is no way back to the open labor market. As many as 19 percent of the Roma population have only completed a special primary school, and another 60 percent have only a primary education. Our school system is one that does not reduce, but on the contrary, increases inequalities among children. It can be said that children from marginalized communities come out of schools even more excluded from the mainstream than when they entered them. (Ministry of Finance, 2020)

Slovakia will have to reconsider the way it integrates its working-age population into the labor market. Not only in terms of increasing the level of activity (participation) and employment rate, but also the length and quality of education with the aim of increasing the competitiveness of the economy. The very low share and insufficient participation of the Roma population in the labor market is not a sustainable development model compared to the model of developed or converging countries.

We need to further develop and, in particular, stabilize those measures that we know are making a positive contribution to closing the gap and increasing the presence of the Roma population in the open labor market. These are measures such as various forms of field social work, support for the local economy and social enterprises, and integration projects in primary schools. However these and other similar measures are now funded mainly by the European funds, which means that they are unsustainable, have outages and do not work effectively.

Today, the Roma population represents the last significant reserve of the Slovak labor force, especially in the East. However, if we cannot get people from Roma communities into the open labor market, this reserve will remain fictitious. If the labor market is to be saved by the Roma children, decent investments must help them first.

***

References:

- Grauzelová, Táňa and Markovič, Filip (2020) Income and living conditions in marginalized Roma communities. Bratislava: Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Government of the Slovak Republic for Roma Communities, p. 18-19.

- Ministry of Finance (2020) Revision of expenditure on groups at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Bratislava: Ministry of Finance, p. 28.

- Šprocha, Braňo (2014) Reproduction of the Roma population in Slovakia and prognosis of its population development. Bratislava: Infostat - Institute of Informatics and Statistics, Demographic Research Center.

- Šprocha, B., Vaňo, B. and Bleha, B. (2019) Regions and districts of Slovakia in demographic perspective. Population forecast until 2040. Bratislava: Infostat, SAS and UK Bratislava.

- Vaňo, Boris (2002) Forecast of the development of the Roma population in the Slovak Republic until 2025. Bratislava: Akty, p. 6.

Anton Marcinčin, Founder, Regional Development Now!

Ábel Ravasz, President, Mathias Bel Institute

Follow us