In the life of an economist, there are some ideas that superficially sound reasonable, but where the reality is much more nuanced and complicated (“taxes always decrease economic activity”, “deficits are bad”, “benefits should be means tested”). But sometimes, one comes across an idea that seems reasonable, but is, in fact, wrong. Because it seems reasonable, it continues to pop up.

This is the case with the idea that Slovak education should be more focused on job skills, that we should listen to employers when building a curriculum, and, preferably, we should decrease the number of higher education students. This is wrong for plenty of reasons, of which I will explore four.

Vocational alumni are no better at finding jobs they studied for

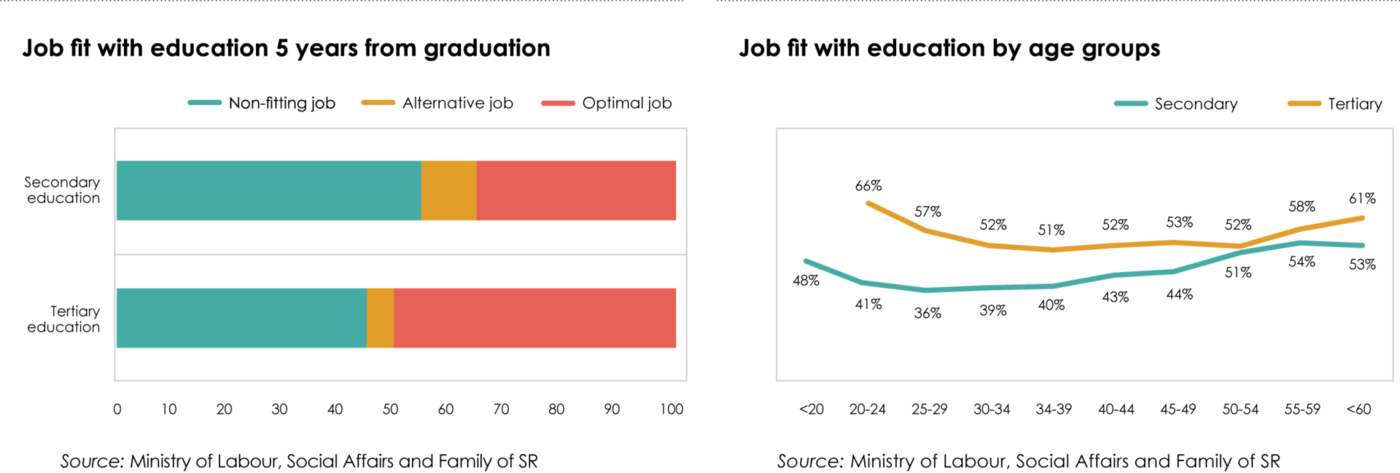

The first directly contradicts the supposed main benefit of vocational education: If we provide job skills in education, students will fit the job market better. Data from the Ministry of Labour shows that this is not true today: 35% of high school alumni work in their area of study five years after graduation, compared with 51% of university alumni. This might seem shocking and untrue, but consider the age when education is chosen: a student picks a high school aged 15, while they pick their university aged 19. By focusing on vocational education, we are giving adolescents a responsibility that is greater than driving or voting neither of which they are allowed at that age.

People, quite simply, live for too long

An important point that often gets omitted in the discourse is that education is a really, really long haul. The difference between high school graduation and pension age is ca. 45 years, and this is the time for which we hope to equip students with job worthy skills. Furthermore, we need to realize, that if we changed the education curriculum today, the first students will finish their education under the new curriculum in 14 years. To understand how much an economy changes in that time: 14 years ago, there were no iPhones, Myspace was the dominant social networking service, and the Great Recession has not yet happened. In other words, in the timespan of an education, the world changes dramatically, and if we look 45 years into the past, when today’s new pensioners started their first jobs, the world is stranger still. In other words, it is simply impossible to provide long lasting job-oriented education.

Companies do not last that long

In addition to preferring vocational education, the argument goes we should invite companies to participate in creating the curriculum. This is wrong for two reasons: first, incumbents will prefer the skills of today and not the skills of tomorrow. For example, if my employer were invited to help create the curriculum, they would focus on skills needed for banking. But banking, while an important part of the economy, is losing jobs rather than adding them and, as much as we hate to hear it, may not be the future engine of the Slovak economy. But the companies that will be the engine may not exist yet or may be too small

Second, because Slovakia is an open economy with plenty of foreign employers, one has to expect that they will not remain on the Slovak market forever. In fact, in the past 15 years, numerous large employers have left Slovakia, or decreased their presence, or went out of business. Simply put, there is a non-negligible risk that companies, who will participate in creating the curriculum, will no longer be around to employ the alumni.

Education should not be only about jobs

It is often unappreciated, that most great education thinkers, like Komenský and Von Humboldt, do not see education as a means to provide job skills at all and were actually opposed to it. They view it almost exclusively as a tool for creating a better and more enlightened citizenry. Even for universities, the primary objective was to produce researchers, the usefulness of the alumni to companies was incidental. There is more to life than jobs; and this is even more true in today’s digital and gig economy, where it is easier than ever to have multiple sources of income. Having a smart, educated and eclectic society is not a less worthy goal than having a productive workforce. It is just a matter of preferences.

What should we do, then?

As Yogi Berra famously said, it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future. As an economist, I can appreciate the difficulty of forecasting and I know how often I get it wrong. If we accept that it is hard to know what skills the economy will require in 15 years, it is virtually impossible for 30 years out. When it comes to education, adaptability is the key. We should, rather than specializing, focus on teaching people to learn: to be able to quickly adapt to different jobs and skills, and to be able to adapt throughout their professional lifetimes. Yes, that means they will require a bit more training today, but their usefulness for the economy will endure, no matter what the economy looks like.

Tibor Lorincz, Economic Analyst, Tatra banka, a.s.

Follow us